Introduction

Bank executive compensation practices continue to evolve, as does the regulatory influence on pay programs. Eight years after the Dodd Frank Act was signed, incentive compensation rules under Section 956 of the Act remain outstanding and seem unlikely to move forward under the current administration. The 2016 re-proposal of Section 956 regulations included prescriptive rules that would have significantly impacted the structure of bank compensation programs. Regardless, banks continue to be subject to the 2010 Interagency Guidance on Sound Incentive Compensation Practices, and the Federal Reserve Bank has enforced many changes on banks $50 billion in assets and larger.

But have things changed enough? The Wells Fargo sales incentive fraud scandal suggests the answer to that question is “no.” A new wave of increased scrutiny on banking compensation practices has emerged, particularly sales incentive practices at lower levels of the organizations. This has spurned even greater focus on clawbacks and forfeitures of incentive pay when fraud, misconduct and bad risk behavior occurs. In fact, forfeiture policies are the fastest growing risk mitigating design feature we are seeing in response to this new crisis.

Incentive Program Evolution

After years of back and forth with regulators, the largest banks appear to have found ways to design incentive plans that balance both shareholder and regulator perspectives. Bank regulators are focused on risk mitigation, prefer less leverage in pay and are more supportive of discretion. They prefer payouts that aren’t based purely on financials and that can be adjusted for riskbased considerations. Shareholders and advisory firms like ISS and Glass Lewis prefer more formulaic incentive plans and are focused on ensuring executive pay and performance are aligned. They support risk adjustments but are more tolerant of leverage in pay plans, if they are used appropriately. As our research shows, pay programs at the largest banks are meaningfully different than smaller banks, primarily a focus of regulatory pressures. We continue to monitor how practices continue to evolve and cascade through the industry.

Pay Mix

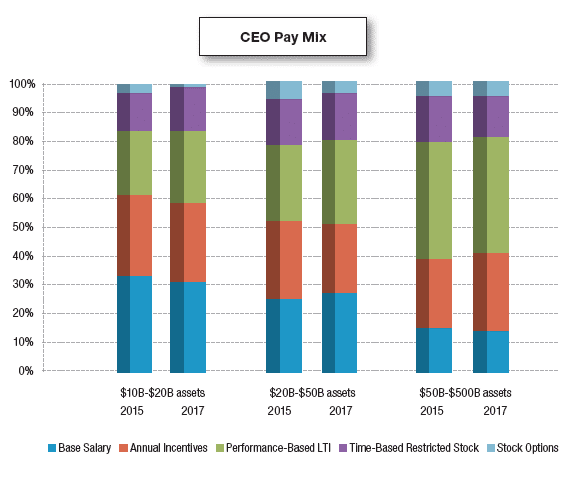

Performance-based compensation continues to be the largest component of pay at all banks in the study. Larger banks typically have a much higher percentage of pay delivered through long-term incentive vehicles (including long-term performance awards, stock options and time-based restricted stock). The use of stock options continues to decline, as regulators view them as adding more risk to the compensation program and ISS, an influential proxy advisor, does not view them as performance-based compensation. Time-based restricted stock continues to remain a modest component that helps retain top performers, encourage stock ownership and lessen the risk of the pay program.

Cash based compensation (base salary and annual incentives) remains relatively consistent over the last three years, averaging about 40% of total compensation for the largest banks and just short of 60% of total compensation at the smaller regional banks.

Annual Incentive Practices

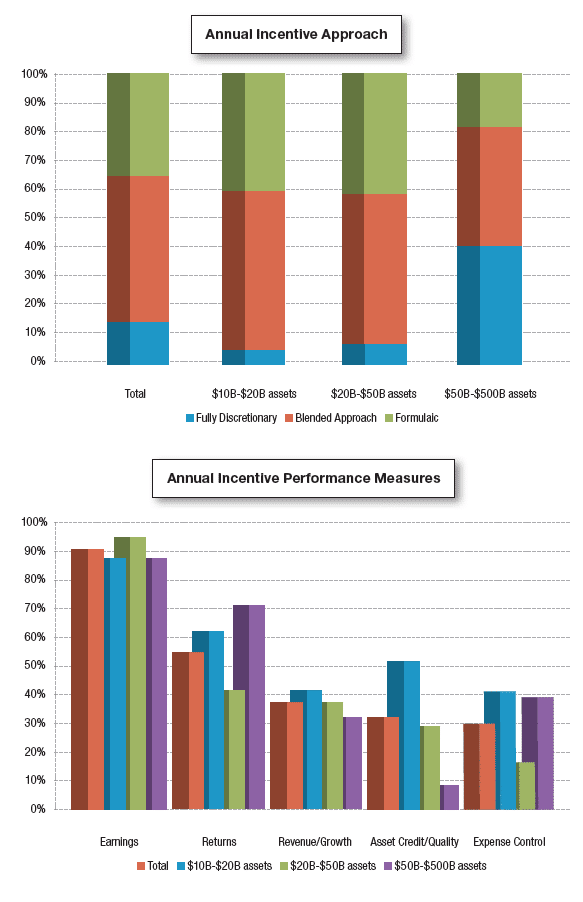

Annual incentives continue to be a key component of executive compensation, but under pressure from regulators have evolved. Contrary to typical practices of other industries and smaller banks, the largest banks are more likely to use a discretionary approach in determining annual incentive awards. Discretion, however, doesn’t mean they don’t have predetermined performance measures or rigorous frameworks for making their decisions. In fact, most use well defined scorecards that incorporate specific risk criteria (sometimes in the form of a defined risk scorecard) in addition to financial and strategic goals for determining payouts. Where discretion is utilized, it is important to consider pay-performance alignment from a shareholder perspective since discretionary plans are often criticized by shareholder advisory firms like ISS and Glass Lewis. If these firms believe that the use of discretion has resulted in pay higher than warranted by a bank’s performance, they are more likely to recommend that shareholders vote against the bank’s Say on Pay proposal. Banks with formulaic plans seek a more direct link between results and payouts, making disclosure and pay-performance alignment seem more direct. However, the more formulaic approach is not immune from shareholder criticism, as it can create challenges in metric selection and goal setting. We are seeing many banks adopt a blended approach, which includes a formulaic component but builds in a discretionary element that includes a broader view of performance and allows for risk adjustments if necessary.

Annual incentive measures continue to focus most prominently on earnings metrics, since they are the primary means for funding cash awards. Returns, growth, asset quality and expense management are other supplemental performance categories. While asset quality measures are least prevalent in formulaic components of larger bank incentive plans, they are often included as part of a qualitative assessment.

Long-Term Incentives (LTI)

Long-term incentives serve a critical role from both a shareholder and regulator perspective, as they motivate long-term thinking, align executives with shareholder interests, mitigate risk taking and provide strong retention for high performers. For these reasons, long-term incentives continue to be the most significant component of compensation for executives.

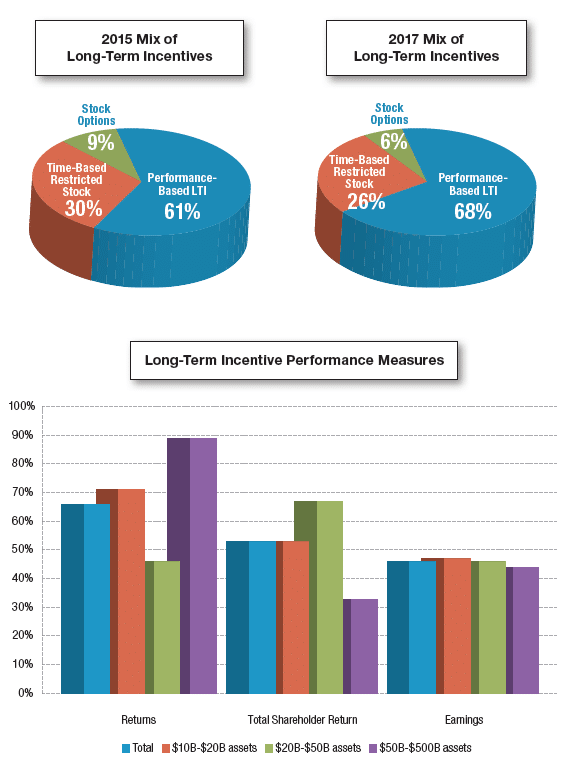

Nearly all banks in the database have some component of performance-based LTI. Over the last two years, the weight allocated to this component has increased to represent over two thirds of the total longterm incentive pay mix.

Two thirds of banks grant time-based restricted stock representing approximately 25% of the value of long-term incentive awards. Time-based restricted stock can play an important role in enhancing the retentive aspects of the compensation program while maintaining alignment with long-term shareholder value. Stock options continue to decline in prevalence and value in the LTI mix.

Return measures (e.g., return on equity, return on assets) remain the most common long-term incentive metric, particularly at banks larger than $50 billion in assets. Total shareholder return and earnings are also common, with the majority of banks using two metrics to provide a balanced approach. Nearly two thirds of larger banks determined payouts at least in part based on performance relative to a peer group of other banks, although regulators prefer that long-term plans not rely solely on relative measures.

Leverage Caps

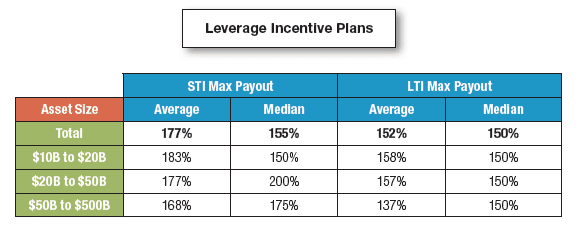

The banking industry continues to receive pressure to restrain upside leverage in executive incentive programs, particularly for long-term plans at banks with >$50 billion inassets. Regulators view the opportunity to earn payouts well above target as potentially promoting excessive risk taking. While other industries commonly provide the opportunity for payouts of two or three times the target amount, incentive plans in the banking industry typically provide lower upside. The median STI maximum payout was 155% while the median LTI maximum has declined to 150% for all bank sizes. This indicates the trend at the largest banks appears to be trickling down to smaller banks. While some large banks initially reduced maximum awards to 125% of target in line with regulator feedback, there now seems to be acceptance from regulators to accept a cap of 150% of target.

Risk Mitigating Policies – The Wells Fargo Impact

Risk mitigation has been a focus of bank regulators since the financial crisis. Incentive plans are reviewed to ensure they comply with the Interagency Guidance of 2010 that requires plans to balance risk and reward and be compatible with effective controls and risk management practices.

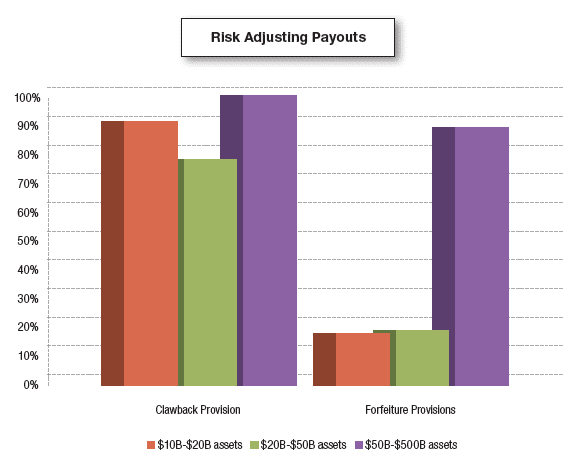

The majority of banks have implemented clawback provisions. Clawback policies provide companies with the opportunity to seek repayment of incentives if it is later determined that financial results were reported incorrectly and/or there was misconduct. While clawbacks are an important and expected governance feature of executive compensation programs, it can be challenging for companies to seek repayment of awards that have already been paid.

Forfeiture provisions, on the other hand, provide companies with the ability to cancel outstanding incentives that have been deferred or remain unvested. Forfeiture provisions are easier to execute, as the company has not yet paid out the incentive awards or released the shares to the recipient. The Wells Fargo sales incentive fraud scandal highlighted forfeiture provisions as a more practical tool than clawbacks for ensuring incentives can be reduced if necessary after the initial award value has been determined.

Forfeiture provisions are common among large banks and we anticipate that their

prevalence will increase among smaller banks and other industries as Compensation Committees seek to have tools to adjust compensation if they discover significant errors or misconduct have occurred. Our research shows a significant change year over year in the prevalence of forfeiture provisions among smaller banks, which coincided with reaction following the Wells Fargo sales fraud scandal. Prevalence among banks smaller than $50 billion increased significantly from 2% in 2016 to 19% in 2017. We expect this trend will continue.

Lessons from Say on Pay

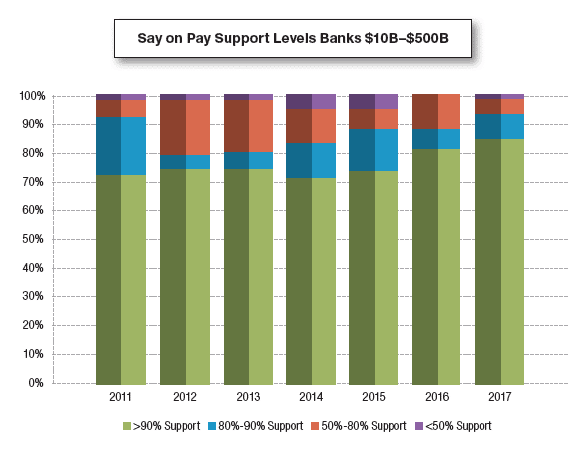

Say on Pay votes have become a regular part of the executive compensation routine for publicly-traded banks. While banks who participated in the TARP program first held Say on Pay votes in 2009, the votes became mandatory for most publicly-traded companies in 2011. Based on a review of Say on Pay results over the past 6 years for banks with assets between $10 billion and $500 billion and our consulting experience, Meridian offers the following observations.

Say on Pay Observations

Banks are getting better at achieving shareholder support for their executive compensation programs. In 2017, 85% of banks in our database received shareholder support above 90%, with a median support level of 96.8%. As shown in the graph above, the percentage of studied banks receiving more than 90% support increased for the third year in a row. Banks, like other public companies, have learned how to align their programs with shareholder expectations and avoid pay practices that can trigger “against” votes.

ISS has significant influence on Say on Pay vote outcomes. While most larger institutional shareholders maintain their own voting policies, ISS still directly or indirectly influences the votes of many shareholders. Over the past 3 years, the median support level for banks in our sample receiving an ISS “against” recommendation has been 70%, well below the median for the entire sample. All banks who failed Say on Pay received an “against” recommendation from ISS, as did more than 75% of banks who passed but with support less than 80%.

While failed Say on Pay votes are rare, they are more likely to occur when shareholders view a bank’s response to a poor vote result in a prior year as

insufficient. Almost all of the failed Say on Pay votes occurred at banks that previously received support below 80%. When a company receives lower levels of support, shareholders expect to see disclosure in the following year’s proxy describing the compensation committee’s efforts to understand shareholder concerns and make changes as appropriate. When this does not occur, shareholders are more likely to vote against Say on Pay the following year and may begin to withhold votes from compensation committee members in director elections.

Say on Pay Myths

While banks have improved in managing Say on Pay, we continue to encounter misconceptions around the process. The following are several “myths” about Say on Pay that do not hold true based on our review of Say on Pay results.

You do not need to be concerned about your Say on Pay vote if you received strong support in the prior year. Banks have experienced significant declines in Say on Pay support from year to year; more than 40% of banks in our sample that have received support under 80% had more than 90% support in the previous year. Market volatility and a decrease in shareholder return relative to industry peers can increase the scrutiny proxy advisory firms use when reviewing pay practices for Say on Pay. ISS has traditionally used one metric, total shareholder return (TSR), when assessing pay-performance alignment. This can create challenges for companies as many pay decisions are made well before year end TSR is known. ISS has started reviewing and considering other performance measures in its qualitative assessment which may help provide more balance in their assessment process going forward. Another area that can create immediate negative results is where companies modify an employment agreement without eliminating problematic clauses or by granting special off-cycle awards viewed as excessive.

If you have a low Say on Pay vote, it is most important to respond to ISS concerns. Many banks often look to appease ISS after a bad Say on Pay outcome, but it is more important to be responsive to the actual shareholders. In our review, we found several examples of banks who were able to earn a “for” recommendation from ISS in the year following a poor Say on Pay outcome, but they continued to receive low support for their pay programs. This suggests that while they satisfied ISS’s concerns, they were unable to understand and remedy the concerns held by another prominent proxy advisory firm (Glass Lewis) and many of their shareholders.

As long as total shareholder return is strong, Say on Pay will not be an issue. While banks with lower total shareholder return are more likely to earn lower Say on Pay support, more than 20% of the banks in our sample who experienced support below 80% had total shareholder return above the median of peers. Even when performance is strong, shareholders have shown a willingness to vote against pay programs they view as inappropriate.

Drivers of Poor Say on Pay Outcomes

While there are numerous factors that can negatively influence Say on Pay outcomes, the following are frequently noted issues leading to low support levels:

High pay levels despite poor shareholder outcomes. Shareholders expect pay and performance to be aligned, and are likely to vote against pay programs when they perceive a strong disconnect. This is particularly true when the Compensation Committee has increased pay through special grants or discretionary increases to incentive payouts.

Lack of strong performance conditions applied to long-term incentive awards. Shareholders expect banks (particularly regional and larger banks) to include strong, multi-year performance conditions on at least half of the long-term incentive awards to better align pay and performance. Where long-term incentives are primarily time-based or based on only annual performance, shareholders are more likely to vote against Say on Pay.

Special one-off awards. ISS and Glass Lewis can be critical of significant onetime awards or grants. They view special awards as generally unnecessary and a sign that the regular program is not working effectively. When a bank views special awards as appropriate to provide, tying them to rigorous performance goals and clearly communicating the objectives and rationale for the awards is critical.

Problematic severance provisions in modified or new employment arrangements. ISS recommends against Say on Pay at any company where a new or modified employment agreement includes provisions they view as problematic such as the ability to receive severance without being terminated or excise tax gross-ups.

Pay philosophies targeting pay above the market median. Shareholders expect pay to be targeted near the median and only provide for above market compensation when warranted based on performance.

Lack of responsiveness to poor Say on Pay vote outcomes. As mentioned previously, shareholders expect banks to proactively seek shareholder feedback and make changes to address shareholder concerns when Say on Pay support declines.

Summary

Whether from shareholder feedback, regulator influence or competitive pressure, one thing is clear—the industry and its compensation programs will continue to evolve and will look very different in the next 5-10 years. The role of Compensation Committees will continue to increase as they seek to ensure incentive programs create pay and performance alignment, attract and retain key executive talent, and mitigate the potential for excessive risk taking.

Meridian will continue to monitor practices of the larger banks and report on their impact as they likely cascade throughout the industry. Please let us know if you are interested in any custom cuts of our 2016 proxy database.

If you have any questions on the issues or data presented in this white paper, please do not hesitate to contact us:

Susan O’Donnell

Partner

Meridian Compensation Partners, LLC

233 Needham Street, Suite 300 | Newton, MA 02464

Office 781-591-5284

sodonnell@meridiancp.com

www.meridiancp.com/insights/financial

Daniel Rodda

Lead Consultant

Meridian Compensation Partners, LLC

400 Galleria Parkway SE, Suite 1170 | Atlanta, GA 30339

Office 770-504-5946

drodda@meridiancp.com

www.meridiancp.com/insights/financial