Competing Pay Perspectives

Posted by Virginia Rhodes on August 28, 2017 in Thought Leadership

CEO pay can be calculated a number of ways—which one is “right?”

CEO pay is on its way up. Again. Or it’s not—depending on how you want to look at it. The release of publicly reported compensation during “proxy season” every year— the period in March and April during which nearly 3,000 public companies file their annual proxy statements—gives corporate critics, defenders and ostensibly objective observers (i.e., the media) a platform and a megaphone to espouse their opinions on what the numbers mean for the corporate world and American society at large.

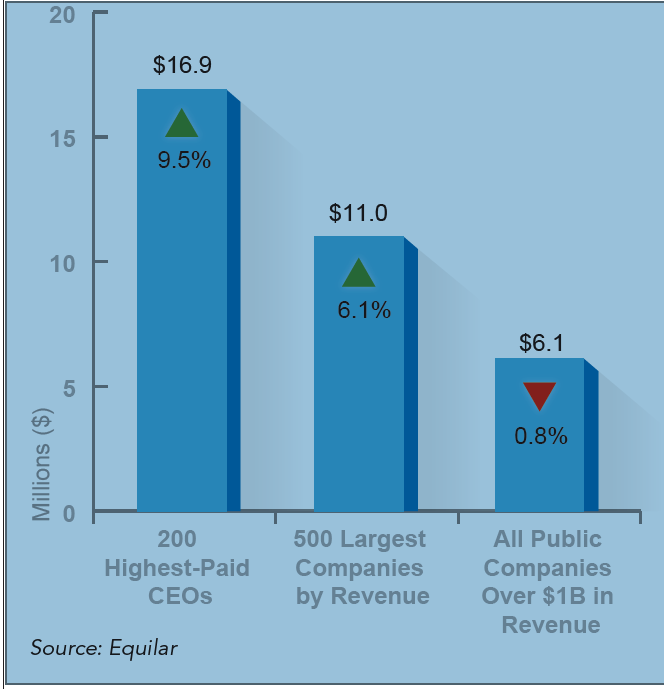

The fact of the matter is that CEO pay is not uniform and straightforward, and it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. For example, let’s look at the following three statements:

1. Median CEO pay increased 9.5% to $16.9 million in 2016

2. Median CEO pay increased 6.1% to $11.0 million in 2016

3. Median CEO pay fell 0.8% to $6.1 million in 2016

Each of these statements is accurate, representing different analyses from the same sample of companies. These three numbers all use U.S. public companies with more than $1 billion in revenue as their base sample size. The first figure represents the median compensation package for the 200 CEOs with the highest-valued pay awards in 2016, according to proxy disclosures. The second number represents the 500 largest companies by revenue, regardless of what the CEO was paid. That means companies like Alphabet, which award their CEOs $1 in salary and stock, would be included, but so are companies like Charter Communications, where CEO Tom Rutledge had a compensation package in 2016 of nearly $98 million. Finally, the last figure represents the median chief executive pay package for all U.S. companies that met the $1 billion revenue threshold—about 1,500 in all.

These three numbers support a popular narrative—pay is going up for the 1% of the 1%. The top-paid CEOs saw significant increases year over year and the largest companies paid their executives more, but overall, wages for the market were relatively flat, even at the CEO level.

Ways to Calculate CEO Pay Complicate the Conversation

On the surface, the perception that pay is on the rise for only the top rung of the corporate ladder isn’t dissimilar from analysis about the difference between CEO pay and that of the average U.S. worker. For example, the AFL-CIO Executive Paywatch counted the ratio of the average S&P 500 CEO to that of the average nonsupervisory U.S. worker, and found a difference of 347:1. With CEO pay reported to the SEC on the rise, and wages generally stagnant, this gap continues to widen and is seen broadly as an indicator of growing wage inequality in the U.S.

Starting in 2018, companies will have to begin reporting the ratio of CEO pay to the median employee in SEC filings—a rule many companies and other corporate governance and executive compensation professionals were hoping would be amended or repealed following post-election changes to the SEC’s membership. At this point, the rule remains on the books, and those responsible for filing proxy statements must make sure they have this information not only calculated, but prepared to be communicated. For most companies, the most difficult conversation will be with the half of their employees who are below the median wage.

Most of the opponents to reporting this ratio are not against addressing income inequality. They are concerned that the way the number must be universally reported will inaccurately show the difference. There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to CEO pay, and there is not a one-size-fits-all employee profile that would make ratios make sense in context. These critics are much more concerned with the fact CEO pay packages are structured quite differently to those of the average nonsupervisory worker, and the way executive compensation is reported to the SEC further complicates that comparison.

Awarded Vs. Actual

The key question to ask when comparing CEO pay value is directly related to what is being measured. For the most part, including in Equilar studies, compensation values cited are from the summary compensation table (SCT) of the proxy statement, which is a mix of both actual pay—base salary, cash bonus and the value of benefits and perks earned in any given year—and an estimated value of any stock or options based on the number of shares in the grant on the day the award was provided.

“Unfortunately, there is no easy way to calculate earned pay when it comes to equity compensation due to the varying time periods over which gains may be realized,” said Virginia Rhodes, a Lead Consultant with Meridian Compensation Partners, who contributed to the recent Equilar report, CEO Pay Trends.

For example, Rhodes noted, restricted stock may vest over a three- or four year period on a prorated or cliff vesting schedule, and stock options also have varied vesting schedules and are even further complicated by the fact that actual gains realized are dependent upon the timing of exercise, which is at the choice of the executive. Performance-based equity grants can typically be earned at more or less than target based on achievement of specified performance criteria (which will vary from one company to the next ).

“As a result of all of this, the figures that appear in the proxy statement can vary widely from what an executive actually earns, and none of these gains [or losses] described ever hit the summary compensation table,” added Rhodes. “Instead, the gains realized for equity grants are reported in the options exercised and stock vested table, which is largely overlooked by most readers.”

A calculation for “realized pay” may provide a more accurate portrayal of what a CEO puts into his or her pocket, and there has been some movement to include these realized values in the proxy statement, most notably through an SEC proposal from 2015 that would attempt to normalize “pay for performance.” The proposed rule, which has remained stagnant for more than two years and seems unlikely to go anywhere, would compare a realized pay figure to a company’s total shareholder return in relation to a peer group.

Like the CEO pay ratio, this standardized ruling across the board would provide a new piece of data never reported by all companies, and may have some unintended consequences. At the very least, realized values may be much higher (or lower) than what is reported in the SCT, which may cause further confusion.

Take for example, Elon Musk, whose reported pay most years is equivalent to the minimum wage in California— in the neighborhood of $46,000 in 2016. Yet, he was fifth on the highest-paid executives in the most recent Bloomberg Pay Index, which put his compensation for fiscal year 2016 around $100 million.

How does this figure arise? Once again, it is completely accurate using a proprietary methodology. There are two key differences in the Bloomberg Pay Index that puts this value into a different stratosphere than what companies report in proxy statements. The article states: “ All equity awards are valued at each company’s fiscal year-end. The index’s figures can therefore differ from those disclosed in filings, in some cases by a lot, depending on stock-price changes and dividend payouts. Recurring annual grants of stock or options are included in the year they’re bestowed, not when they vest. One-time grants, meant to pay an executive for several years, are allocated over the life of the award as explained in regulatory filings.”

That means in Musk’s case, part of his total compensation figure in the Bloomberg Pay Index includes one-tenth of a 10-year, 5 million- plus share option grant awarded in 2012, valued at the stock price on Dece mber 31, 2016. When that award was granted, the company’s stock was less than $30. By the end of last year, the stock value was over $200. (It’s also worth noting that since then, the stock has skyrocketed to nearly $400, meaning that the value of any options vested would be significantly more today.)

Musk’s options award was initially reported in 2012 as $78.1 million in grant-date value for all 10 years, as reported in the proxy. For 2017, if valued at the $375 stock price where the shares were hovering when this article was written, the value of one-tenth of the award would be $197,625, 000.

Companies Must Tell Their Own Pay Story

Ultimately, Musk’s scenario is a good example of how the philosophy behind CEO pay has evolved in recent years. While the nuances of how pay is awarded, reported and eventually paid is not a simple relationship to explain, the underlying reasoning for how it works has good intentions.

Public companies are beholden to create shareholder value, and the public markets are built on that foundation. That’s why pension funds and large asset managers whose investments are heavily concentrated in retirement funds like 401ks are becoming more active and vocal. These funds are responsible for growing the investments of millions upon millions of individuals. And how do these

investments grow? Through long-term company performance.

Since the introduction of Say on Pay in 2011, a mandated shareholder advisory vote on executive compensation, pay philosophy has evolved to align better with shareholder return. Along with that, disclosures about pay have also evolved. Companies are seeing increasing pressure from their shareholders not only to address problematic pay practices but also to ensure that they are including detailed enough information so that shareholders will be able to make informed votes.

“Although many companies dread the Say on Pay vote each year, overall, the changes that have occurred because of the enacted legislation can be viewed positively in many regards,” said Meridian’s Rhodes. “All of these changes have made organizations more forthcoming with disclosure describing the rationale for pay actions and more accountable for paying leadership teams only when warranted—or else suffering the potential consequences.”

In the end, those who want to criticize or defend CEO pay will be able to use numbers to their advantage—a feature that isn’t unique to CEO pay, of course. Statistical analysis is notoriously repurposed to support any agenda as seen fit, and particularly when you have large CEO compensation numbers compared against a stagnant wage in the U.S., the potential for scrutiny ratchets higher.

The onus is on all stakeholders in corporate America—boards, executive management, investors, customers, employees, the media and the general public—to seek out available information to carry on a constructive conversation about how executive pay and wage inequality are interrelated. It is also the board and management’s responsibility to communicate this information to these constituents in the clearest ways possible through the avenues they have—public filings, internal communications, and the like—to ensure that they have the opportunity to tell their own story before someone else tells it for them.

CONTRIBUTOR

VIRGINIA RHODES

Lead Consultant, MERIDIAN COMPENSATION PARTNERS

To view this article and the entire issue of Equilar’s C-Suite magazine, visit http://www.equilar.com/c-suite/downloads.html.

Compensation Benchmarking, Regulatory Issues & Compliance