Daniel Rodda

Daniel Rodda

Jinyoon Chung

Jinyoon Chung

Introduction

This is Meridian’s fifth year tracking executive compensation practices at U.S. banks with assets above $10 billion. One theme remains consistent: programs continue to evolve. As we entered the 2018 year, companies invested much time and energy calculating the CEO pay ratio and preparing for its disclosure. The Tax Cut and Jobs Act eliminated the long-standing practice of deducting performance-based pay for covered executives, while providing tax benefits to companies and individuals. The impact of these changes may not be fully known for a few years.

In the meantime, our consulting with clients and analysis of this year’s database indicates continued adjusting of incentive plans, primarily in the area of metric selection and goal setting. Proxy advisory firms continue to focus on incentive plan design features and resulting pay-for-performance (PFP) alignment. ISS updated their 2018 PFP quantitative test approach and there are signals that more changes may be in store for 2019. While the significant majority of banks received Say on Pay support higher than 90%, the number of banks below that level increased in 2018. Additionally, recoupment policies continue to evolve and the banking/financial services industry leads the way by expanding the triggers and recoupment definitions to include misconduct and reputational risk triggers.

The remainder of our white paper provides a summary of trends over the past year as well as commentary on additional key issues being discussed in boardrooms.

The Year in Review

Annual Incentive Practices

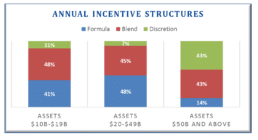

Short-term incentive program designs are generally consistent with last year, as banks have already adapted to regulator and shareholder preferences. Practices continue to reflect company size, business strategy and compensation philosophy. The largest banks (assets greater than $50 billion) typically use programs with at least some degree of Compensation Committee discretion (i.e., fully discretionary or a blended approach using both payout formulas and Committee discretion). Although discretionary, such programs often rely on financial scorecards, strategic/individual goals and/or risk-based performance criteria. This allows Committees to 1) assess a broader view of performance to reflect the complexity of their organizations, 2) consider both actual results and “how” they were achieved and 3) recognize the economic environment in which they occurred. Discretionary plans require Committees to effectively manage pay-for-performance alignment and communicate the rationale for pay outcomes to shareholders. Such discretion is not as common among banks with assets under $50 billion.

The majority of smaller banks continue to use more formulaic approaches or a blended approach of formulaic and discretionary measures. Consistent with prior years, ISS and Glass Lewis continue to scrutinize discretionary programs and prefer more formulaic plans regardless of company size and complexity.

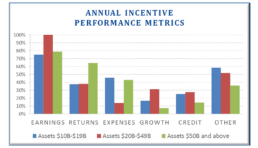

Earnings measures (e.g., earnings per share (EPS), net income) continue to be the most common performance measure in annual incentive plans, although a majority of larger banks continue to include returns, particularly return on assets (ROA) and return on equity or tangible equity (ROE/ROTCE). Among smaller banks, there was a shift from growth measures (e.g., revenue, loans) to expense control over the last year, as well as an increase in the use of strategic and individual measures. Goals are typically assessed on an absolute basis reflecting internal budgets/plans, although a recent trend has been an increased use of relative measures to mitigate the challenges associated with setting goals. Many larger banks incorporate relative performance within discretionary plans, while others use relative performance formulaically. When selecting performance measures, banks should give consideration to how success is defined both internally as well as in communications with shareholders.

Proxy advisors are also increasingly scrutinizing performance goals, consistency of measures year to year, and commenting on “goal rigor.” This focus makes it important to provide disclosure around the goal setting process – particularly if goals are lower than prior year results, or if measures are changed.

Long-Term Incentive (LTI) Practices

While the structures of long-term incentive plans have stabilized, many banks continue to refine performance measures and goals to ensure alignment with shareholders and strategic priorities.

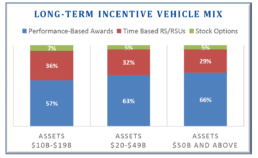

Banks continue to use a portfolio of LTI vehicles to meet multiple objectives and provide a balanced approach to rewarding long-term performance. Proxy advisors and shareholders continue to favor performance-based programs to increase pay-for-performance alignment. Over 90% of banks in our database now include LTI awards with performance-based vesting conditions (e.g., performance shares, cash), and these awards now make up more than one-half of LTI awards for each of the size categories in our database. Share-based plans remain the majority practice, with only 7% of banks using cash-based LTI plans.

On the other hand, the prevalence of stock options, which are not preferred by regulators, and not viewed as performance-based by proxy advisors, continues to decline as banks replace them with performance awards and/or time-based restricted stock.

Time-based restricted stock and restricted stock units (RSUs) continue to account for approximately one-third of banks’ LTI programs, with three-year ratable vesting being most common.

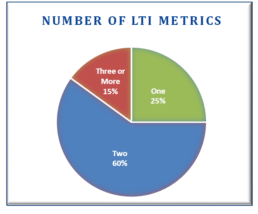

75% of banks in our database utilize at least two performance measures to ensure LTI programs support the company’s financial and strategic goals.

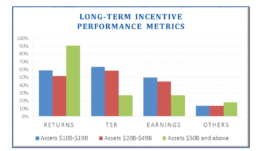

Returns-based metrics (e.g., ROE and ROTCE) continue to be the most prevalent performance measures used by the banks with assets of at least $50 billion. Smaller banks tend to include total shareholder return (“TSR”) more frequently, along with returns and earnings metrics.

Relative metrics are common in LTI plans, reflecting the challenges banks face in setting long-term goals as well as a desire to align with shareholders who consider relative performance for their investments. An overwhelming majority of banks use the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles as the threshold, target and maximum performance levels for relative performance plans, despite proxy advisory firms advocating for target performance goals to be set higher than the median.

Most banks with relative LTI metrics compare their performance to an index or broader group of banks (52%) or their compensation peer group (42%). Only a small number of companies compare performance to a custom performance peer group (8%).

Incentive Plan Leverage

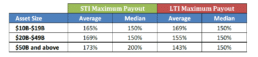

For annual incentive plans, the median maximum opportunity is 150% of target. Among larger banks with specified maximum payout levels, a slight majority use maximum awards of 200% of target.

Similar to last year, the median LTI maximum payout opportunity is 150% of target. Several larger banks, who previously adopted a 125% of target maximum under regulatory pressure, have recently increased their maximum to 150% of target as regulatory pressure has eased.

Consistent with prior years, 50% continues to be the most common payout threshold in both annual and long-term incentive plans.

CEO Pay Ratio

The CEO pay ratio disclosure was arguably one of the biggest issues faced by public companies heading into the 2018 proxy season, as reactions were uncertain. However, after much planning and preparation, the response was muted and few companies received any backlash on their ratio.

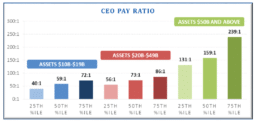

As expected, the larger banks reported significantly higher CEO pay ratios (median ratio of 159:1) relative to smaller banks in our sample (median ratio of 67:1). Consistent with other industries, this difference was driven by the size of the company with CEO compensation higher at the larger banks than smaller banks (median pay of $12.0 million vs. $3.5 million, respectively) whereas median employee compensation was more comparable (median pay of $63,000 vs. $56,000). Bank ratios paled in comparison to other industries, notably retail, which disclosed ratios above 1,000:1 in some cases.

Say on Pay

While most banks continue to receive strong Say on Pay support, the industry did experience a decline in results during the 2018 proxy season. Of the banks in our database (>$10 billion in assets), 79% received support above 90% in 2018, compared to 86% last year. While failures continue to be rare, three of these banks received support under 50% in 2018 compared to one in 2017 and none in 2016. Given the decline in shareholder returns for the industry so far in 2018, more banks may struggle with Say on Pay in 2019 as shareholders evaluate whether pay aligns with performance.

Where banks received low support for Say on Pay in 2018, contributing reasons included:

■ CEO pay and performance misalignment;

■ Failure to respond to reduced Say on Pay support;

■ Outsized special awards;

■ Incentive goals not seen as sufficiently rigorous;

■ Performance-based equity grants with a one year measurement period;

■ Largely discretionary and/or lack of clear linkage to financial performance criteria; and

■ “Problematic pay practices” such as large, one-time equity grants and excessive retirement payments.

It is important for companies who experience a decline in support to show responsiveness to shareholder concerns with meaningful shareholder engagement and disclosure of the process, findings and changes (as appropriate) in the following year’s proxy.

Developing Practices and Key Issues

The following section summarizes a few topics that we continue to see in practice and discussions with our clients.

Recoupment Policies

The financial industry continues to reassess recoupment policies. Despite the lack of final regulations on the Dodd-Frank Act clawback requirement, recoupment policies have become mainstream practice.

Recoupment policies most commonly include clawbacks, which provide for companies to seek recovery of incentives already paid. These policies have generally been designed with the original Dodd-Frank Act proposal in mind, which focused on excess incentives paid during the three-year period prior to a restatement. Forfeiture provisions, which provide for unvested and/or deferred compensation to be forfeited, have increased in prevalence following the fraudulent sales practices at Wells Fargo.

Over 90% of banks in our database have formal clawback policies and over 40% have forfeiture provisions, although specific designs vary. Recoupment policies generally provide the Compensation Committee with discretion to determine if a clawback or forfeiture is appropriate, if certain triggers occur and if the amounts are significant. These triggers generally fall in one of the following three categories:

Financial Restatements and/or Inaccurate Performance Measures

Sarbanes-Oxley introduced clawbacks for financial restatements resulting from executive misconduct. Restatements resulting from misconduct continue to be the most common trigger in clawback policies. However, increasingly companies are including not just financial restatements but any miscalculated financial measure used to determine incentive payouts. Further, many policies allow Compensation Committees to consider a clawback even if the incorrect financials were not the result of misconduct, in line with the proposed rules under Dodd-Frank.

Misconduct

Companies are also exploring other misconduct scenarios, such as fraud, negligence (including in a supervisory capacity) and/or violation of company policies that do not necessarily lead to a financial restatement. Equity awards often include “termination for cause” provisions that result in forfeiture of outstanding awards. Many companies are reevaluating their definitions of “cause” to ensure they are not overly narrow. Where misconduct must lead to harm to trigger cause, companies should evaluate whether reputational harm is considered in addition to financial harm. Additionally, companies should consider whether to include the “reasonable potential” to cause harm in addition to actually causing harm. Companies should also ensure that any special retirement vesting provisions for incentive awards would be superseded by a termination for cause.

Risk-Related Triggers

Forfeitures may be triggered by failure to comply with risk or compliance policies, or if financial performance declines significantly (such as negative net income) suggesting that prior risks were not properly assessed. When evaluating policies, banks should also consider to what extent they will apply to supervisors of individuals who violate policies. While risk-related triggers are most commonly tied to forfeiture provisions, some policies also allow for potential clawbacks for significant violations of risk policies.

Mergers and Acquisitions

2018 has seen an increase in merger and acquisition activity within the banking industry. Banks making acquisitions face several issues within their executive compensation program.

Incentive Plan Goals

Banks should consider in advance how acquisitions will be treated when determining performance for incentive plans. Most incentive plans will exclude expenses related to acquisitions and integration from results in incentive plans, but banks should also consider whether adjustments will be made for earnings and dilution resulting from unanticipated acquisitions during the performance period.

When an acquisition is known before the performance goals are established, typically goals are based on the deal pro forma. Committees and management should be clear on what items are included in the pro forma and what may lead to adjustments when payouts are determined. Acquisitions can also increase uncertainty around setting performance goals, which may make it appropriate to widen the range between the threshold and maximum performance goals.

Special Awards

Questions often arise as to whether special bonuses should be paid for the effort leading up to, or integration of, acquisitions. Shareholders are generally skeptical of merger-related incentives for executives, particularly when awarded before results of the acquisition are known and/or before shareholders have seen any increase in value from the transaction. Generally speaking, if special awards are warranted they should be tied to synergies realized after the deal closes and should focus on individuals most directly responsible for the transaction and integration.

Peer Groups and Market Data

Executive compensation is strongly correlated to bank size, which is why peer groups generally focus on banks of similar asset size. Following acquisitions, banks will need to reevaluate their peer group based on their larger size and complexity. Highly acquisitive banks may need to adjust their peer group each year as they grow. Additionally, executive roles often change with acquisitions, requiring benchmarks to be adjusted to reflect new responsibilities as well as bank size.

Retirement Provisions

Equity (and long-term cash) compensation is a significant component of executive pay programs. As baby boomers retire, companies are paying more attention to how such programs treat retirement.

Many companies do not include specific provisions addressing the effect of retirement, which can lead to treating retirement like voluntary termination, generally resulting in forfeiture of the award. Some companies are reassessing their practices and considering whether retirement provisions would enhance the effectiveness of their long-term incentive programs. Three factors are driving the need to review retirement provisions:

1. Increased use of performance shares;

2. Continued motivation of executives as they approach retirement; and

3. Desire for well-planned succession/transitions.

Now that performance shares represent the greatest portion of equity awards for many banks, equity treatment is more complex. Given the typical performance award reflects three-year cliff vesting, how do banks continue to motivate and reward senior executives in the last few years of employment if they do not expect to receive full value from their equity grants? A forfeiture approach may be perceived as unfair. Vesting treatment can also create unintended consequences for succession planning and treatment of pay in executives’ final years.

Retirement provisions should be driven by an organization’s business strategy, culture and values. As a result, there is significant variation in market practices. The primary decision points include:

■ Proration vs. Full Vesting – One decision is whether equity award values should be prorated for time served or paid in full. Proration can be on the front end of the grant if a specific retirement date is known in advance, or more commonly at the actual retirement date, based on the amount of time employed during the performance period. With prorated awards, executives receive an award value proportionate to their employment service. However, some banks provide full vesting of awards, particularly when LTI grants are viewed as compensation for the prior year’s performance.

■ Immediate/Accelerated Payment vs. Continue to Vest – Another decision is related to the timing of the award and whether shares are delivered immediately on retirement or on the original vesting schedule. Continued vesting has become a common practice that can benefit the bank and the executive by rewarding the executive for facilitating a strong succession transition. Continued vesting is particularly important for performance-based awards to ensure that payouts are aligned with active employees. Such a practice can help reinforce non-compete or non-solicit agreements as the bank can cease vesting if the executive violates the restrictive covenant.

■ Retirement Definition – The retirement age definition is another key feature to consider. Age 65 is common, as are age plus service (e.g., age 55 and 10 years’ service) or a total age and service model (e.g., age and service of 75). Retirement age definitions and equity treatment can also be a key consideration if recruiting senior-level executives (age 55 and older).

Special Equity Awards

In our consulting, the use of special equity awards outside of the normal compensation program is sometimes raised. While there are situations where supplemental grants can be appropriate, it is important to take a planned and strategic approach to any special awards. This is particularly critical when grants are considered for Named Executive Officers as proxy advisory firms like ISS and Glass Lewis are typically critical of such awards.

The presence of supplemental equity awards, in combination with pay-for-performance misalignment, can result in an “Against” vote recommendation, and in some cases result in a Say on Pay failure. Many investors believe that ongoing executive pay programs should be designed to reward and retain top performing executives without the need for special awards.

Before granting supplemental awards, companies should consider the following:

■ Are current incentive pay opportunities competitive?

■ Are the “right” performance measures being used to reward performance?

■ Is there appropriate leverage to align pay with performance (without promoting excessive risk-taking)?

■ Have actual payouts resulted in appropriate pay/performance alignment?

■ Does the compensation program provide sufficient wealth accumulation opportunities?

■ Do executives have meaningful retention hooks (i.e. unvested equity)?

■ Do executives maintain appropriate stock ownership?

These considerations provide important context for assessing whether the current program is meeting desired objectives or may warrant change, as well as provide rationale for any supplemental award.

If supplemental awards are granted, proxy advisory firms and investors may be more supportive if the grant is performance-based. The challenge will be determining the performance measure(s) and disclosing how they coordinate with existing performance measures. The value of the award should also consider existing pay opportunities, current company performance and the impact on the pay-for-performance analyses conducted by ISS and Glass Lewis. Shareholders will expect increases in executive pay be aligned with higher levels of performance. High-performing companies will receive less scrutiny of such grants than lower performing companies.

Supplemental awards should be approached with an awareness of these issues and companies should be prepared to provide clear disclosure of the rationale and how such awards align with shareholder interests.

If you have any questions on the issues or data presented in this white paper, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Susan O’Donnell

Partner

Meridian Compensation Partners, LLC

233 Needham Street, Suite 300

Newton, MA 02464

Office: 781-591-5284

sodonnell@meridiancp.com

Daniel Rodda

Partner

Meridian Compensation Partners, LLC

400 Galleria Parkway SE, Suite 1170

Atlanta, GA 30339

Office: 770-504-5946

drodda@meridiancp.com

Jinyoon Chung

Senior Consultant

Meridian Compensation Partners, LLC

233 Needham Street, Suite 300

Newton, MA 02464

Office: 781-591-5280

jchung@meridiancp.com

Stephan Bosshard

Senior Consultant

Meridian Compensation Partners, LLC

200 Park Avenue, Suite 1700

New York, NY 10166

Office: 646-737-1640

sbosshard@meridiancp.com